Performative practices in the process of healing the trauma of history ►►►

The effects of war go very far. In the 1970s, American doctors and scholars determined its influence on human soma and psyche as PTSD – posttraumatic stress disorder. This term resulted directly from the observation and diagnosis of American veterans of the Vietnam War 1957–1975. Today, it is known that PTSD is passed down from generation to generation. In some cases, it can even affect great-grandchildren.

World War II marked the lives of our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents with the stigma of suffering. This suffering was so severe that it often took its toll many years after the war had ended. It manifested itself in the form of diseases, premature deaths and suicides. It happened because the next totalitarian system imposed upon us after the war was – to say it gently – not conducive to convalescence after trauma. Or rather, it effectively strengthened and perpetuated its consequences.

To be honest, I do not know any family that would not have lost at least one of its members during the war. Most often there were several relatives killed or murdered. For this tragic reason, the continuity of the family was disrupted, weakening the intergenerational bond. Sometimes many branches of a beautiful and thriving family tree disappeared so rapidly that it brought the whole line to a definitive annihilation. Often it was of a noble lineage. This is also what happened in the matrilineal branch of my family. My grandfather lost three brothers and two uncles. He himself was to be shot in Piaśnica, but fled and fortunately escaped that fate…

In the light of the aforementioned events, the destruction of the Polish social elite during Inteligenzaktion in Piaśnica affects me not only as a historical fact and a terrible fate. It touches me painfully and deeply as evidence of the banality of evil. People did this to people, neighbours to neighbours. And there is no exaggeration or pathos in this conclusion.

There are families that were not treated so cruelly by war. But in these homes, please forgive me the wording, there may hide “a corpse in the closet”. It makes itself known during the day or in a dream of “that damned war”, taking the form of pictures, sounds or smells.

BODY MEMORY. ANCESTRAL MEMORY

Initiating the process of healing the trauma of history through individual and group performative practices.

Programme of the workshop:

- the experience of the body as a habitat of feelings and imagination, in the process of working with the body – individually and with the group;

- discovering the hidden meanings of souvenirs, photographs and other objects found in the family archives – individual work;

- body memory – body work devoted to discovering the so-called old corporeality – corporeality of parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, great-great-grandparents…;

- an attempt to create a solo performance show with the conscious use of the body, voice and various objects;

- reminiscences of World War II in 20th-century art, in Poland as well as in the World (J. Grotowski, T. Kantor, J. Szajna, A.Wróblewski, Z.Nałkowska, T.Różewicz, A.Kiefer, J.Beuys, K.Vonnegut) – lecture and short summarising discussion.

Workshops Body Memory – Ancestral Memory took place in October 2017 and in September 2018, at the Przebendowski and Keyserlingk Palace in Wejherowo and at the Krokowa Castle in Krokowa. They were attended by members of the Scientific Society of Sociology, students of the Pomeranian University in Wejherowo. The workshops were conducted in cooperation with the Włodzimierz Sedlak Foundation as part of the project Piaśnica – Kultura Miejsca / Piaśnica – Culture of Place.

Performative practices in the process of healing the trauma of history ►►►

TO EXPRESS THE UNSPEAKABLE

Reflections on psycho-somatotherapy of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of Iraqi war veterans.

The vast majority of peacekeeping missions soldiers experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. They faced them during the missions and after returning from them. As it is commonly known, a good soldier should be courageous, prideful and resistant to stress. According to a certain cultural canon, these special features testify to his belonging to the world of real men. Therefore, those soldiers who were not injured and did not suffer visible and serious bodily harm suffer without complaint. They would rather draw a veil of silence on the trauma they have suffered rather than admit their own weakness. It’s a matter of their honor. I would like to emphasize that the therapist’s task is not to judge such an attitude, but to understand it. The patient’s inexpressible pain always deserves respect. Regardless of his deeds, glorious or damnable.

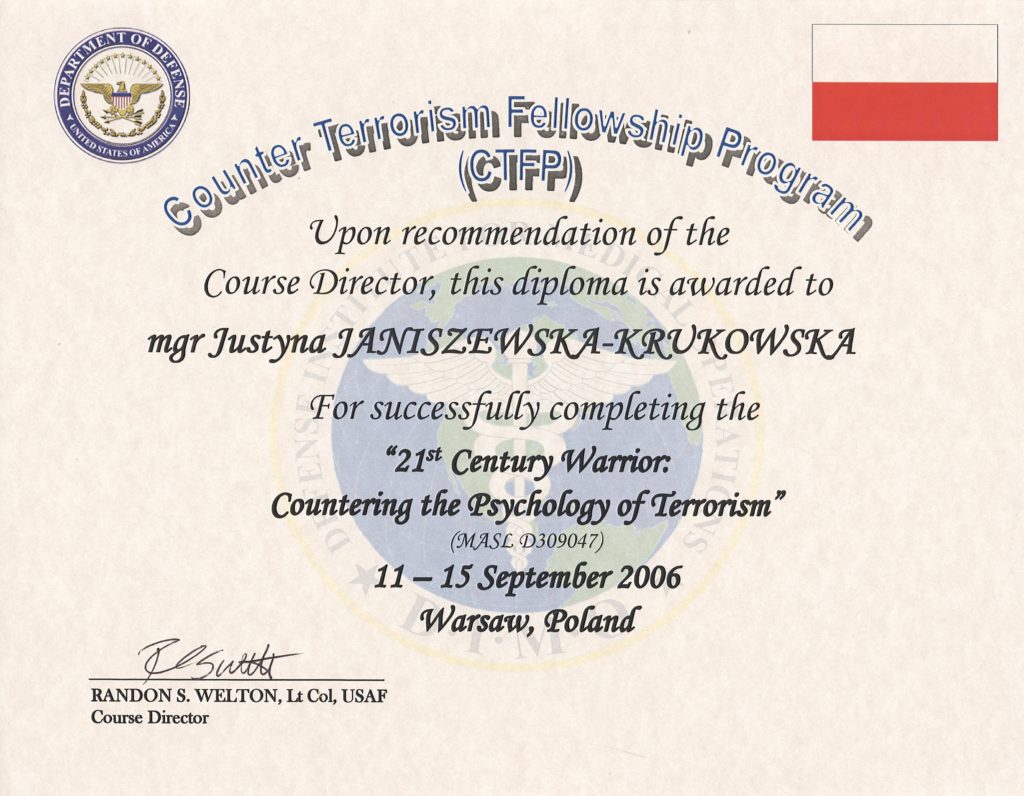

In 2006, as a debuting therapist, I had the opportunity to help veterans of the Iraq war, with physical and mental injuries. It became possible thanks to the initiative of a well-known Polish military psychiatrist, Prof. Stanislaw Ilnicki, the founder and first director of the Combat Stress Clinic in Warsaw. As part of seven-day rehabilitation stays, I worked with a group of about 10 people in the afternoon. In the morning, a team of psychologists dealt with them, focusing on the verbal therapy. The main idea of my work was to create such conditions where non-verbal communication would be possible. As it soon turned out, it was a very good idea. Firstly, because the soldiers were quite exhausted after a session lasting several hours where they talked about their traumatic experiences from the Iraqi war. Second, because unlike the female and three male psychologists, I was the only woman in my therapy room. The only one and, in addition, young.

What would young men, veterans of the Iraqi war, want to share with me? With their own problems or weaknesses? According to what I wrote in the introduction about the male and soldier’s sense of honor – it was not possible. They had other needs. They wanted to reveal to me the feelings hidden during the war, at least for a moment. Also the erotic ones… Already during the first relaxation session, hearing quiet conversations about what they dreamed last night, seeing the eyes of my special patients staring at me, I had to face the phenomenon of transference. Its consequence was the phenomenon of my countertransference.

I have already used many methods in my therapeutic practice. However, their number was not so important. It was important to select them properly and to combine them appropriately. For the first time in my practice, I introduced individual and group performative practices. They were not directed at psychodrama or at recreating the trauma. They appealed to the untold and hidden resources of my patients’ psyche and soma. My task was to gradually and gently revive the feelings that seemed to be hidden in their bodies as a result of the traumatic experiences, which were expressed through movement, facial expressions, gesture, sight, touch. In individual work, I used the EMDR behavioral method, according to F. Shapiro. I also used the method of free visual associations with the help of spontaneous drawing expression.

I realized quite quickly that I had to take special care of my comfort after each work session. Working with patients suffering from PTSD requires immediate supervision. The therapist should care about himself/herself when such help is not available. Post-traumatic stress is contagious. I found out it by observing the behavior of my colleagues working with patients suffering from PTSD.

To conclude my reflection on the psychosomatotherapy of Iraqi war veterans, I would like to quote a short fragment of the Japanese fairy tale “Tsukina Waguma”. I took it from a novel by C.P. Estés “Women Who Run With the Wolves”. This famous Jungian psychoanalyst learned the main theme of the fairy tale thanks to a WWII veteran during his stay at the Illinois Veterans Hospital.

The desperate wife of a soldier suffering from post-traumatic stress turns to an old medicine woman for help… “My husband came back from the war terribly changed”, she complained. He is always angry and doesn’t eat anything. He doesn’t want to go home and he doesn’t live with me the way he used to. Will you give me such herbs for him to be good and loving again as before.” A shaman recommends the woman a trip to a high mountain. There she must obtain just one hair torn from the white crescent on the black bear’s neck. Fulfilling the order seems to be almost a miracle. However, the woman carry out it, bravely facing all the troubles and dangers of the expedition.

Does the fairy tale tell about the miraculous power of a plant or object? No, it is rather about what women or man should do to achieve a healing miracle – so to do what is a seemingly impossible. She must consciously, courageously and with great determination submit herself to the process that leads to the unknown. Well, therapy is like embarking into a journey whose essence and outcome remain a mystery until you immerse yourself in it.

Contemporary psychiatrists, psychologists and psychotherapists have theoretical knowledge about the causes and effects of PTSD. They also have a certain range of resources and methods of treatment. Unfortunately, the conventional approach, focused on treating symptoms – mainly with pharmacotherapy, still seems to dominate the complementary approach. Military psychiatrists willingly use also tools based on technology, including video of combat stress simulators. Verbal group psychotherapy is also popular.

I believe that instead of forcing the only one method, we have to use the variety of forms and methods in PTSD treatment. It is important to appreciate the multiplicity and complexity of forms of therapy oriented not to immediate effect, but toward work in the process. There is an urgent need to turn up to integrative medicine. According to its philosophy and practice, every human being on a deep organic level is the indivisible unity of body and spirit. Post-traumatic stress ruins this unity. And if it’s left untreated, just like depression, it settles in the body permanently. Therefore, in order to sensibly help victims of post-traumatic stress, we should return to body psychotherapy. As a practicing psycho-somatotherapist, I see this domain as a valuable and vital branch of modern integrative medicine.

The drama of the war in Ukraine and the common fear for peace in the world mean that, in addition to the military combat arsenal, we must improve and mobilize the entire arsenal of therapeutic measures and methods. Specific techniques of body psychotherapy could be a method of rapid post-traumatic intervention. Deactivating the trauma almost in nascence, promotes quick recovery after it went through.